|

Saint John of the CrossLife, Poetry & Teachings of Saint John of the Cross (1542-1591) Copyright © 2006 by Timothy Conway

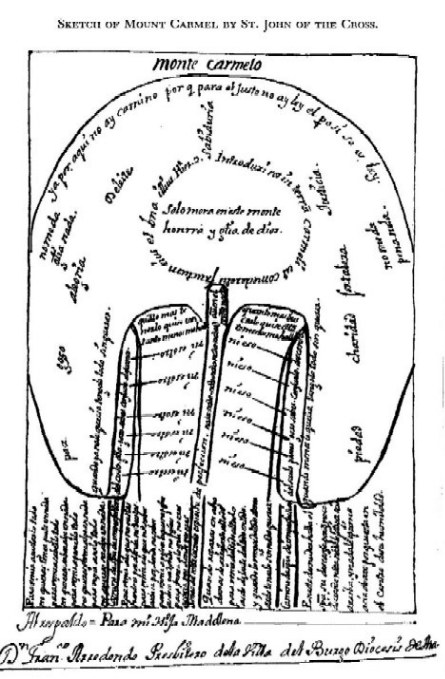

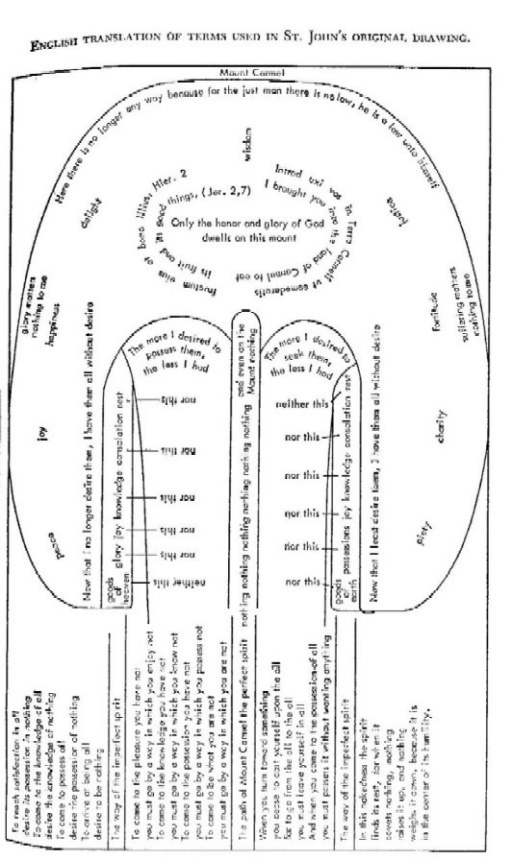

San Juan de la Cruz / John of the Cross (1542-91) is one of the towering saints in Christian history and often considered, even by secular poets and scholars, to be the loftiest Spanish-language poet ever. He is also regarded as Catholicism’s “greatest mystical theologian” and an eminent Doctor of the Church as well. His prose works display a remarkably wise understanding of various extremely subtle nuances of psychological and spiritual development. It is said that “no other writer has had greater influence on Catholic spirituality.” He was born Juan de Yepes y Álvarez, circa June, 1542, the youngest of three sons to a noble family of Fontiveros in old Castile (c100 miles northwest of Madrid). His father was a wealthy silk merchant, his mother a poor weaver girl. The family elders disowned John’s father for marrying beneath his station and he died shortly after Juan’s birth. At age 9, Juan joined his mother and siblings in moving northeast to Medina del Campo. He was boarded in an orphanage school from age 10. When he was 12, he fell into a deep well and was saved from sinking and drowning by finding a piece of wood to hold onto that came to him after he prayed to Mother Mary. She had earlier saved him when, as a tiny boy, he had fallen into a pond at Fontiveros. Rather inept in apprenticing as a carpenter, wood sculptor and then printer, from 1557 onward John worked compassionately as a hospital nurse among advanced, horrible cases of syphilis. Beginning in 1559, still working as a nurse, he made use of the chance to receive a higher education in Catholic lore and the humanities at the Jesuit college in Medina del Campo. In 1563, the quiet, shy, intensely pious young man entered the Carmelite Catholic religious monastic order. From 1564 to 1568 he studied theology at the famous university of Salamanca, with its 7,000 students and eminent professors. Juan de San Matías, as he was now known, was ordained a priest in 1567. He was 25. In summer 1568 Fray Juan joined the illustrious and dynamic saint Teresa of Ávila (1515-82) at the Carmelite priory of Medina; the two set off with Teresa’s nuns northward for Valladolid, where she was to establish a convent of her new Discalced (“shoeless”) Carmelite reform movement. The Carmelites had originally been founded as a community of hermits in Palestine in 1185, but in the next century had transformed into one of the four orders of itinerant, mendicant friars (including, most notably, the Franciscans and Dominicans). In 1432 the Carmelites adopted a more lax way of life, which prevailed until Teresa’s reform, which based itself on an older, stricter “rule of St. Albert” from 1247. In addition to stressing poverty, strict enclosure, and reduced hours of sleep, one of the austerities introduced by Teresa and her nun-colleagues was a special kind of frequent if not total “fasting”: abstention from animal flesh—i.e., they ate only a spare vegetarian diet. Above all, these Discalced Carmelites put a special emphasis on the contemplative life of solitary, meditative “mental prayer” over communal vocal prayer. That summer of 1568, 26-year-old John learned from his older mentor Teresa (then 53) all about her new movement. In a letter written in September she notes, “… though he is small of stature [not quite five feet tall], I believe he is great in the eyes of God…. He is sensible and well-fitted for our way of life… There is not a friar but speaks well of him for he leads a life of great penitence… We have never seen the least imperfection in him. He has courage, but, as he is quite alone [the solitary male member of Teresa’s reform movement at this point], he needs all that the Lord gives him.” After that initial period of contact, John and two other friars who joined him set up the first male house of the Carmelite reform in a lonely, half-ruined cottage at Duruelo, a few miles from Juan’s birthplace at Fontiveros (halfway between Ávila and Salamanca), next to a willow-lined stream, meadows, and views of the Sierra de Gredos mountains. The three friars created out of the derelict space a tiny chapel, choir, a few hermit cells, and, as stated by one of Juan’s best modern-era biographers (upon whom I mainly rely), Gerald Brenan: “Here, with stones for pillows, their feet wrapped in hay, among … crosses and skulls, the friars remained praying from midnight to daybreak while the snow drifted through the tiles onto their clothes [a white serge cape over a coarse brown habit]. They ate from broken crockery and drank from gourds; their only other possessions were a few books, some scourges [for self-administered penance and sharing in Jesus’ suffering under the Romans—a common medieval practice for devout Christians] and bells and five hour-glasses [for precisely regulating their schedule].” (Brenan, p. 15) The holy friars’ presence soon attracted many visitors, including John’s mother, brother and sister-in-law, who helped them in doing manual labor chores. John’s preaching in town on the holy life of joyous surrender to God and interior prayer drew a number of men to join the friars. So much so that after 18 months, the burgeoning band had to move to a larger building at Mancera, a nearby village. Meanwhile the Discalced Carmelite reform was spreading, raising up many houses in Spain and beyond. At one point Fray Juan was sent by Teresa to bring sanity to a situation at the new priory at Pastrana, 40 miles east of Madrid, where friars and townsfolk had become too enamored of an unbalanced, overly-penitential woman of visions and miracles, Doña Catalina. In April 1571, John was appointed rector of a Discalced Carmelite college at the university of Alcalá near Madrid; but with John’s shy personality and preference for meditation over friend-making and fund-raising, it didn’t prosper. In September 1572, John was brought by Teresa to serve for the next five years as a confessor and spiritual director, along with another friar, for the 130 nuns at the Convent of the Incarnation in Ávila. Teresa had spent over 20 years here before she launched her reform. The nuns violently, vehemently resisted her being appointed by a papal official as their new abbess. But Teresa’s loving warmth and natural humility won them over, and with John’s help, the spirituality of the majority of the women blossomed. Fray Juan took up residence with another friar in a small house adjoining the convent (on the grounds of an old Jewish cemetery where lay buried Moses de León, author of the foundational kabbalist work, the Zohar). John, writes Brenan, “had had no contacts with women [outside of family] up to this time—now he was surrounded by them. As the last twelve years of his life were to show, he felt a sympathy for them that he did not so easily feel for men, unless they were much younger than himself [and open to learning]. Most of those he now saw in the confession box would have been very ordinary girls… while others would have had a genuine bent for the religious life. He seems to have treated the first gently, making allowances for their limitations [“the holier a man is,” John wrote, “the gentler he is and the less scandalized by the faults of others, because he knows the weak condition of man”], yet leading them gradually towards more serious views by stimulating their desire to be better, while the latter he directed along the thorny road of mental prayer. Another of his gifts was for casting out devils, by which was meant treating cases of possession and hysteria…. His success in this … gave him a great reputation in the city, while the nuns of the Encarnación, who were witnesses of his austerity, regarded him as a saint.” (p. 24) As for his relationship with Teresa, they mutually benefited. She likely lent him books banned by the Inquisition as “Illuminist” (Alumbrado), e.g., treatises on mystical theology and contemplative prayer by Francisco de Osuna, Bernadino de Laredo and García de Cisneros, that had influenced her development. She was recording her own reflections on the Song of Songs and three years later began her famous work Interior Castle. He conversed with her every week in the convent parlor and heard her regular sacramental confession. A certain tension sat in those early years between them, for the gregarious Teresa needed and was deeply attracted to men like the young friar Gracián who could serve as a more dynamic and winning public face for the reform movement. John was a bit too contemplative for her at this time in her life. She once jokingly remarked, “If one tries to talk to Padre Fray Juan de la Cruz of God, he falls into a trance and you along with him.” The quip nevertheless reveals his spiritual power. Teresa, an expert judge of human character and holiness, soon came to regard Juan as an authentically God-realized saint. And “towards the end of her life we find her twice begging Gracián—in vain, for he was jealous—to send Fray Juan back to her in Castille [as her spiritual confessor and director].” (Brenan, p. 24) Though their work went splendidly well at the Incarnation Convent, “the fame and success of Teresa’s reform had raised against her a host of enemies of whom the most bitter belonged to the unreformed body of her own order,” says Brenan. This included Fr. Rubeo, the Carmelite general superior, who reversed an earlier approval of the Discalced reform and put all their houses under Calced Carmelite rule, denouncing the reform friars and nuns as sinful rebels. Yet the papal nuncio and king still approved of the reform. Juan was kidnapped at one point by members of the anti-reform Calced Carmelites who didn’t want to see their lax, easy lives challenged; he was imprisoned at Medina del Campo for a few days until the nuncio’s order released him and some other captive friars. But then the nuncio died and was replaced by a man hostile to the reform. The reform friars were all to resign any offices held and turn them over to the Calced. None obeyed. John and his friar colleague at the Incarnation Convent were ordered to return to their own former houses. They refused and had the further audacity to support the candidacy of Teresa (then at Ávila) for re-election as prioress of the convent while the laxer group of nuns and male officials wanted someone else. On Dec. 2 or 3, 1577, John was captured by an armed posse and incarcerated in a 6x10 foot dungeon-like closet at the Carmelite monastery down in Toledo. Teresa wrote impassioned letters to the king and the archbishop to free him, declaring that John was and had always been a saint. But to no avail. John was accused before a tribunal of rebellion and disobedience, terrible sins. He replied that he was only following the direction of the apostolic visitor, his immediate superior. He spent the next nine months in hellish conditions—damp frigid cold that winter, stifling heat in the summer, darkness which badly strained his eyes (the only opening was a two-inch horizontal slit near the ceiling), lice infestation, dysentery from the stale scraps of sardines and bread, and vomit-inducing stench due to the fact that his hateful jailer would only change his waste bucket every several days. Not least was the constant humiliation and frequent torture from fellow “Christian” friars, who took him out a few times each week into the rectory at mealtimes, where he was made to kneel like a dog and endure much verbal scorn and bodily flogging and caning for daring to help launch the reform with Teresa. Many of the younger friars revered him as a saint, but their strict vows of obedience rendered them powerless to alleviate his condition. The period was especially hard on Juan because his own great humility made him begin to seriously doubt himself—perhaps he was only a stubborn rebel, sinfully proud in helping Teresa. Such thinking only increased his anguished sense of isolation. Yet it was during this Dark Night of the Soul (he apparently coined the phrase), this period of being stripped of all material and spiritual consolations, this being “totally undone and re-fashioned in God,” that Juan issued forth the early verses of some of his major poems. A new jailer had come in after six months, and given John a fresh tunic and a pen, ink and small notebook for “composing a few things profitable to devotion.” Juan fell into ecstasy one day contemplating the deeper spiritual significance of a love song he heard a young man singing in the city street: “I am dying of love, dearest. What shall I do? –Die.” The first part of his Spiritual Canticle poem and other verses soon followed, and more flowed out over the next several years. Poetry for Juan was not an art-form but a vehicle to express, using the typical medieval “bridal mysticism” themes, his intense realizations of the transpersonal God, his love for the personal Lord, and the blazing power of Spirit, which had stoked a profound fire in him, overcoming the interior and exterior darkness of his dire situation. In August of 1578, a disconsolate and disabled Juan enjoyed a vision of Mother Mary, who had twice saved him as a boy from drowning, now “filling the cell with her beauty and brilliance, and [she] announced to him that his trials would soon be over and that he would leave the prison.” In mid-August, Juan was lucky to escape from his hell-hole in the wee hours of a full-moon night, dismantling at last the cell’s padlock with a needle and thread given by the jailer, and making use of a fabric rope he had fashioned with some scissors and carpet-strips also given by the jailer, to slide down over a balcony onto a high wall, narrowly avoiding fatal injury. In his terribly weak state, he found help again from Mother Mary to somehow scale a remaining wall and find himself on the street beyond. After taking cover, first at a tavern and then the front hall of a caballero’s mansion, John found shelter the next day at a Discalced Carmelite convent. The good nuns smuggled their gaunt, disfigured guest off for six weeks of recovery at the hospital and then private home of Don Pedro de Mendoza, a wealthy friend of the reform. In early October 1578 Juan made the difficult, 100-mile donkey ride to Almodóvar for a chapter meeting of the Discalced Carmelites. All were shocked to see the emaciated appearance of the 36-year-old friar, “like a dead man, with nothing but skin on his bones, so drained and exhausted he could hardly speak.” For safety, he was made temporary head of a priory-hermitage off at remote Calvario. It lies at the eastern border of Andalusia in southern Spain on the upper flow of the Rio Guadalquivir, amidst rocky hills covered with pines and aromatic shrubs. At this simple religious house, a converted farmhouse with a few acres of orchard and farmland, and a tree-shaded spring, John spent the next eight months until June 1579, probably the happiest time of his life. He would take the thirty friars out under the trees and, instead of giving them Bible passages upon which to meditate, speak to them of God’s wondrous glories manifest as nature and all creatures before sending off into the surrounding area for their solitary periods of long meditation on God. John sometimes took odd moments to weave willow baskets or carve small wooden images, or make religious drawings. The restful, contemplative hours, the fresh air, and the simple vegetarian diet of vegetables, salads and bread strengthened him enough that he could take up an added duty—confessor to the nuns at the convent of Beas de Segura, a few miles away. Teresa had written to its prioress, Ana de Jesús, about John, calling him “that divine and heavenly man. I assure you, my daughter, that since he left these parts, I have not found another like him in the whole of Castile, nor one who inspires souls with such fervor on their journey to Heaven. Only consider what a great treasure you have in that saint and let all the sisters in your house talk with him and confide in him about their souls. They will then see how much good it does them and advance rapidly in spirituality and perfection, for Our Lord has given him in this a special grace…. He is indeed the father of my soul and one of those with whom it does me most good to converse. … He is very spiritual and has great experience and learning.” (Quoted in Brenan, p. 44) So every Saturday, John and a companion trudged the six-plus miles to the convent, where John heard private confessions all day into the next, and celebrated mass for them and, in the parlor with the assembled community of nuns, presented Gospel passages along with his lucid mystical commentaries before heading back to Calvario. He gave the nuns his schematic drawings of Mount Carmel, with a “map” of the virtues, and corresponding maxims of spiritual counsel. [See image below, with similar image giving the maxims in English translation.]Nuns made copies of his little book of poems, and he explained the verses with commentaries.

Brenan notes that “these visits to the nuns of Beas made a profound impact on Juan de la Cruz’s life and work. After his harsh sequestration in prison the tender and delicate intimacy that grew up between him and these sisters of his order supplied something that he was badly in need of, while their questions and demands gave him the stimulus to write his prose works in the form of explanations of his poems…. He continued to write to and visit these nuns of Beas for many years after he had left their neighborhood.” (pp. 45-6) In 1580, the Vatican granted the Discalced Carmelites the right to erect their own province, though complete independence and recognition of the two groups, Calced and Discalced, would not come until 1593. Teresa’s reform had been spared destruction. In June 1579 Fray Juan, was appointed rector of the new Carmelite college at the thriving city of Baeza, 36 miles further down the Guadalquivir on a long spur of high land. “He at once found himself caught up in a life of great bustle and activity. Besides teaching and receiving visits, he was much sought after by devout persons of both sexes who were anxious to have him as their spiritual director.” (p. 47) The monks, priests, nuns and laity who had the good fortune to come under his spiritual direction at all these places over the years loved Fray Juan for his profoundly inspirational and clarifying wisdom and his gentle, shy kindness. John, in turn, loved them all, and tended their spiritual development with great attentiveness, a sensitivity combined with candor. He also lovingly tended their bodies, such as during the terrible influenza epidemic of 1580. Yet he craved for more time in silent, formless contemplation of God. He tended to fall into deep ecstatic raptures during this time, and was often concerned that this should happen while saying mass—which it did. He still took time to visit the Beas nuns for several days every few weeks, intoning psalms or singing his own songs along the way. Sometimes he stopped en route to teach the monks at a Trinitarian monastery the art of inner contemplation, also retreating into their belfry to quietly contemplate the lovely countryside and the even greater beauty of God. He also liked to spend days at a time in nature with a brother friar at a small farm, donated to the college, overlooking the Rio Guadalimar. There he meditated, prayed and sometimes sang in the meadow beside a small stream, often long into the night. Such love of nature, notes Brenan, was rare for the city-dwelling Spaniards of that era. Juan was made prior of Los Mártires down south in Granada. He first went to Ávila to pick up Ana de Jesús, who had been designated new prioress of a convent in Granada; here he saw and conversed with Teresa for the last time. Juan, Ana and their party arrived in Granada in early 1582 after a perilous journey and here he stayed continuously for the next three years and much of the next three years after that. He counseled the friars and novices, and, as at Calvario, took them out for long outings into nature, giving talks before each man would find a solitary spot for an hour or two of meditation. Sometimes they had to look for him and tug on his habit to bring him out of his deep contemplative raptures. On feast days he told them amusing stories to make them laugh, a balancing levity for the otherwise harsh life of poverty, deprivation, self-denial and inner focus. John was always on the lookout for any signs of depression in his students, and, though he was rather solemn, he wanted them to stay light and joyous in their Lord. For all his contemplative depth, he was not a quietist, and enacted along with his charges a good amount of manual labor to stay active and grounded—quarrying stone, masonry work, gardening, washing clothes, cleaning the priory, preparing food, etc. As for penances, a standard feature of medieval devotion, he led the way, taking the smallest cell, selecting the lowliest chores like cleaning the latrines, and commonly eating only bread and herbs, letting the friars eat more diversely and supplement this on non-fasting days with chickpeas, rice and a little fish. (The sick were allowed to eat even more to maintain strength.) On Fridays, Juan went around before meals to kiss the friars’ unwashed feet and then, after the meal, obliged them to strike him in the face as they left so he would not feel proud in being their prior. One lighter element from this period is that Juan installed his brother Francisco as mason and gardener and loved to hear him sing the popular love songs that Juan then reframed with a deeper spiritual meaning, a lo divino. It was while taking in the gorgeous views from the spur on the Alhambra hill where the priory sat that John wrote the bulk of his long prose commentaries on his poems, clarifying the way of ego-death, transcendence and union, “participation in God.” These include the twin volumes Ascent of Mount Carmel and Dark Night of the Soul, on the poem of the latter name; The Spiritual Canticle; and a later poem and commentary, The Living Flame of Love. John’s colleagues and disciples recall their mentor to be, in Brenan’s words, “unobtrusive, silent, with downcast eyes that hid the inner fire[;] he looked as if he had no other wish than to pass unnoticed and unconsidered through the world.” He had a round face, big brown eyes, a broad forehead, and aquiline nose, and had gone prematurely bald. Brenan notes how “the extreme introversion and love of being alone which had characterized his youth had been succeeded by a stage [noticed at Calvario, Beas and now Granada] in which he liked to be surrounded by those who were committed to the same road as himself.” At Granada, one of his disciples was Juan Evangelista (d.1638), who became his secretary and traveling companion and one of the better sources of information about John’s habits and character, as was Mother Ana de Jesús (d.1621), who lived with her nuns just a five-minute walk from Los Los Mártires, and whom John visited to hear confessions and give instruction every few days beyond the double grille segregating them for propiety. “The nuns worshipped him,” we hear. “When on one of his … visitations he was admitted to the enclosure, they would fall on their knees and kiss his hands or his feet.” He still traveled from time to time up to Beas and he presided over a new convent for nuns at Málagra. Nearly all these sisters were Castilian. A new DC vicar-general, Nicholas Doria, an authoritarian man, began to vie with Gracián, who still held administrative power, in making certain changes to the Order after Teresa’s passing, changes John did not appreciate (like sending out missionaries to Africa instead of focusing on contemplation of God, and having officers and confessors be appointed instead of elected at the local level), and he argued as such at the chapter conferences at Almodóvar in 1583, and at Lisbon and Valladolid in 1585. At Lisbon, John also presciently went on record to state that one Sor María de la Visitación of Lisbon, a beautiful young visionary claimed by her followers—including high-ranking churchmen—to have powers of healing, bodily levitations, and displays of light during her raptures, and who later allegedly developed the stigmata wounds of Christ, was actually a fraud. John was later proven right about the stigmata. He had always warned his charges to be very careful about any consolations and powers that might dawn, since their source could be demonic. In Oct. 1585, Juan, in addition to his duties in Granada, was appointed vicar-provincial of the order in Andalusia. “He now had nine priories to visit regularly, to which were soon added three more, the most notable being that of Córdoba… Besides these, he had some half a dozen convents of nuns to keep an eye on…. A rough calculation shows that in the curse of these two years he must have traveled over six thousand miles…. Except when his journey was short, he went on horseback.” He mortified himself wearing hair shirts and spiked chains that dug into his flesh, aggravated by travel. For inspiration, he read the Bible or sang from the Song of Songs. He also went into rapture states that sometimes knocked him off his horse. After this grueling administrative post was finished, John returned as prior to Los Mártires, but was soon made deputy vicar-general, second in command to Nicholas Doria, and so he was brought up to Segovia (the Order’s administrative seat) for three years beginning in 1588, and made prior of a nearby Discalced Carmelite house. Juan spent long hours in contemplation here, either at the windows of his tiny cell overlooking the trees and river, or in a low grotto blocked by bushes and brambles on the side of a cliff, or in a garden hermitage, or, on summer nights, just laying under the trees all night long without sleep, listening to the river and songbirds. He shrank from business, sometimes saying, “For the love of God, let me be, for I am not fit to deal with people.” The inner focus on the formless God appears to have taken predominance once again in his life. “It always seemed that his soul was at prayer,” recalled one nun. He was often observed knocking his knuckles hard against the stone wall to bring back an awareness of the body so that he could better relate to the physical world and its human inhabitants. He had much business to conduct—administrative matters, instructing the friars and the nuns at a nearby convent, and writing correspondence (most of his letters, including those to St. Teresa, were later burned by nuns under duress from his enemies). He was only averaging about two hours of sleep each night. Disagreements with Doria and his consulta and others in his camp, who wanted more and more authoritarian power, led to Juan’s resisting them more and more, especially over the rights of the nuns to choose their own directors and keep their constitution so carefully written by Teresa. He saw it as a matter of social justice and did not mince words. He opened his address at the chapter general meeting in June 1591 with the words, “If at Chapters, assemblies and meetings men no longer have the courage to say what the laws of justice and charity oblige them to say, out of weakness, pusillanimity or fear of annoying their superior and consequently not obtaining office, the Order is utterly lost and ruined.” (Quoted in Brenan, p. 72) But none would agree with him, all taking the side of the feared Doria, and John was thereupon stripped of being a deputy-general, a definitor, a consulta member, and even a prior, and banished as a simple friar to the poor hermitage of La Peñuela, the loneliest of all the houses, near Baeza in the Sierra Morena. The ultimate intention was to ship him across the ocean to Mexico. Juan was actually happy to be relieved of so many duties. While he waited for two months at a priory in Madrid, he was repeatedly reprimanded in public by its head, the new deputy general. John bore it all in silence. He had never shown any animosity to his enemies, even back in 1577-8, and had never raised his voice in annoyance or lost his calm composure. He wrote to Ana de Jesús, new prioress at Madrid, “Now that I am free and no longer have charge of souls, I can, if I so wish, enjoy peace, solitude and the delectable fruit of forgetfulness of self and of all things, while for others it is well that I should be out of the way….” To another prioress he equanimously wrote, “one must not blame men for these things since it was not they who caused them, but God, who knew what was best for us.” The move to defame him and expel him altogether from the Reform he had founded with Teresa was gathering strength. After six weeks at La Peñuela, during which time he instructed the friars at the behest of the friendly prior, did some preaching at a church not far away, and immersed himself in raptures out on the heath under the trees, in September he fell quite ill with fever. His body was worn out after having long suffered the ill effects of his earlier imprisonment and now had little resistance. He was urged to seek medical attention at Ubeda, 35 miles away; he left on Sept. 28. The callous prior there put him in the worst cell. At one point, Juan’s whole leg broke out in ulcers, and a surgeon extensively cut and probed, causing intense pain, which he bravely bore without complaint. His health grew worse. Tumors broke out over his body—he would only mutter, “more patience, more love, more pain.” John had long been linked with miracles, such as divine fragrances, occasional bodily levitations, clairvoyance, gift of prophecy, control over storms, etc., all of which he tried to dismiss. Now the Divine aromas were often perceived around him, and the friars and local people openly regarded him as a saint. But the prior’s heart remained closed; he repeatedly scorned Juan publicly, refused him visitors, and complained bitterly over the “expense” of caring for him. On the night of Dec. 14, 1591, John humbly begged forgiveness from the man for having caused so much trouble, and the prior, realizing John’s true holiness and his own terrible mistake, wept. At 11:30 that night, Juan joyfully sat up in bed and declared, “How well I feel.” He asked that the 14 friars be called. “The hour is approaching.” They recited some hymns and, at his request, verses from the Song of Songs. “What exquisite pearls!” he declared. They left him alone save for an attendant. The church clock struck midnight, the hour for matins. “Tonight I shall sing matins in Heaven.” This amazing mystic poet, author and spiritual director then folded his hands and stopped breathing. He was dead at the age of 49. Crowds, hearing of his death, came and tore off parts of his clothes and bandages—even some of his hair and nails and a toe—as holy relics, so obviously infused was he with the Spirit of God. The same behavior occurred the next day at his funeral, despite attempts by friars to protect his body. Dug up from the grave nine months later with the intent of sending the corpse to Segovia, his body was found to be undecayed (“incorrupt”) and wonderfully fragrant, like the remains of certain other saints in the Catholic and other traditions. His body was then split up, the relics sent to various Catholic sites for veneration, where they began to display miraculous healing properties. Brenan and the other biographers note that it is actually well that John died early and still in Spain, not Mexico, otherwise his life would have ended in disgrace and both he and his lofty writings would have been almost completely forgotten, damned as heretical. But the collecting of affidavits from eye-witnesses to his saintly life began in 1614, 23 years after his passing, and continued until 1627. The first biography on John was written by a priest in the Order of Discalced Carmelites, Fr. José de Jesús María (Quiroga), at Brussels in 1628, followed by the best of the early works, that by Fr. Jerónimo de San José, OCD, at Madrid in 1641. This priest had collected many of the depositions for John’s beatification. The more notable of the Spanish-language biographies since then are those by Carmelite fathers Bruno de Jesus Marie, OCD (Paris, 1929), Silverio de Santa Teresa, OCD (Burgos, 1936), and, especially, the one compiled by Fr. Crisógono de Jesús, OCD (Avila, 1940). The first edition of John’s poetry and prose works, not quite complete, came out in 1618, followed by other editions over the next several decades, all part of the beatification process to expose and assess his views. His teachings were soon vehemently opposed by the Inquisition in Spain and by the Vatican as guilty of the “illuminist” heresy, but were vigorously, successfully defended in 1622 by an Augustinian friar, Basilio Ponce de León, professor of theology at University of Salamanca. (The first critical edition of Juan’s works was released in 1912-1914 at Toledo, since then superseded by an even more precise edition, the one made by Fr. Silverio de Santa Teresa, OCD [Discalced Carmelite vicar-general] in 1929-31.) John was beatified in 1675 by Pope Clement X, at last silencing his detractors. He was fully canonized a saint by the Church in 1726, and two centuries later, in 1926, declared an eminent, authoritative Universal Doctor of the Church, as was St. Teresa herself in 1970. These last 400 years, Juan’s poetry and prose teachings on the way of negation (via negativa), the art of formless contemplation, and the spiritual union or marriage of the soul in the Divine Beloved have been highly influential, for both orthodox Christian contemplatives and for those branded heretics (e.g., Illuminists and Quietists). The voice of Juan de la Cruz still speaks to us today of the dazzling glory of God, beyond all forms, images and limits, the Living Flame of Love, the only beatitude and fulfillment for each and every soul.… Those with ears to hear, let them hear. + + + + + + + Works of John of the Cross Juan’s three most famous poems are The Spiritual Canticle (39 verses), The Dark Night (8 verses), and The Living Flame of Love (4 verses). John wrote other notable poems and, as mentioned, four books of prose commentary on his three major poems. He wrote a few shorter prose items including letters of spiritual counsel, and made some illustrations, too, such as his famous image of Jesus on the cross [see below], and his oft-copied schema on the Ascent of Mt. Carmel (an allegory for mystical spiritual life), composed of maxims for the dedicated aspirants—especially the nuns—under his direction. All his works were composed in the last 14 years of his life, and are filled with wisdom and psychological depth. Influences on John’s theology and mysticism include not just the Bible, on which he was an expert (both Hebrew Tanakh and Christian New Testament), but also Augustine, Aquinas, Bernard, Victor, the Rhineland Mystics who were so inspired by Meister Eckhart of Germany (Tauler, Suso, Ruysbroeck), and the aforementioned medieval Spanish mystic sources. The much earlier figure, pseudo-Dionysius Areopagite (c500), is clearly a major influence, too.